“Natura maxime miranda in minimis” (“Nature is greatest admired in the tiniest things”) is an expression attributed to Linnaeus – who in turn took it from Plinius the Old – that describes very well the wonder one feels when observing the marvellous and tiny complexity of organisms such as lichens.

Not all the lichens are microscopic, but it happens that also in groups characterized by conspicuous and showy species, like genus Cladonia, there can be also more discreet species, which risk to remain overlooked just because of their inconspicuous size.

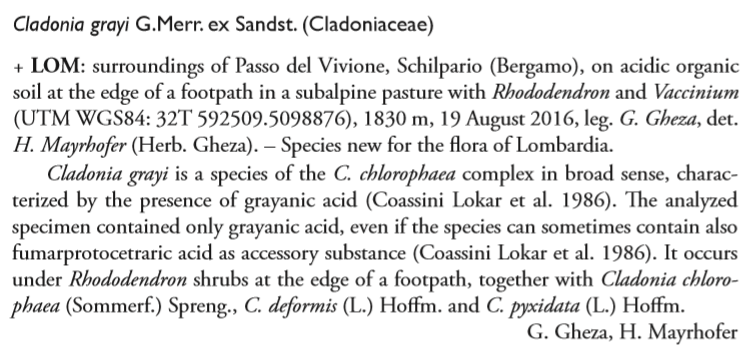

Among these species we can find Cladonia peziziformis, a very tiny and often unnoticed species which is currently rare and threatened in the whole of Europe, to the point that it is protected in some Countries, e.g. in Great Britain, where it is considered a priority species (Chambers 2003) assessed as critically endangered (Woods & Coppins 2012).

This lichen has lilliputian podetia, generally not taller than a half centimetre, and, since it grows directly on soil, it can be quite difficult to notice. One could therefore think that its putative rarity in Europe is due to this difficulty of detection, but instead it is actually rare and declining, mostly because it is closely bound to specific habitats which are declining as well, i.e. heathlands (Tønsberg & Øvstedal 1995).

Until few years ago, in Italy this species had been reported only from Liguria, but recently it has been recorded in several sites of the western Po Plain (Piedmont and Lombardy) in which Calluna vulgaris-dominated heathlands and/or acidic dry grasslands still occur (Gheza 2018, 2020; Gheza et al. 2019a), which confirmed its bond to such endangered habitats.

Cladonia peziziformis

A similar species which can share the same habitat is Cladonia cariosa, that is however far more widespread in the whole of Italy and Europe. We could say that where we find C. peziziformis also C. cariosa is very likely to occur, but not vice-versa.

So far, the most interesting sites where observe both the species together were located along the upper Sesia rivercourse (Gheza et al. 2019a; Gheza 2020), but unfortunately the anomalous flood of October 2020 buried under about a metre of pebbles and debris most of the dry grasslands located near the riverbed, causing a considerable decrease in the number of occurrence sites of both the species in the Sesia river valley. Which, of course, upset me.

Cladonia cariosa

Almost like a sort of ‘compensation’ from the karma, however, during one of my last inspections in the Ticino river valley on account of the Life Drylands project for which I am currently working, I accidentally found a new occurrence site of both the species in a small patch of acidic dry grassland.

The curious thing is that the last time I explored that grassland – right seven years ago, during the fieldwork for my MSc thesis – it was almost devoid of lichens! Just few thalli of the commonest species occurred – C. foliacea, C. rangiformis, C. rei. Instead, now 8 species of Cladonia occur, among which C. peziziformis and C. cariosa, which were absent seven years ago.

The grassland in which I have recently found Cladonia peziziformis within the Parco Ticino Lombardo (Lombardy Ticino Natural Park); even if it seems not exactly a biodiversity-rich habitat in its winter look studded with withered grass tufts, it is actually an important habitat for many organisms, not just for lichens.

Both these species had already been reported from the Ticino river valley (Gheza 2018; Gheza et al. 2019b); in spite of this, the discovery of this new site, considering also the relevant extent of the colonies, is surely an important information to know and take in account for future conservation planning.

Cladonia cariosa

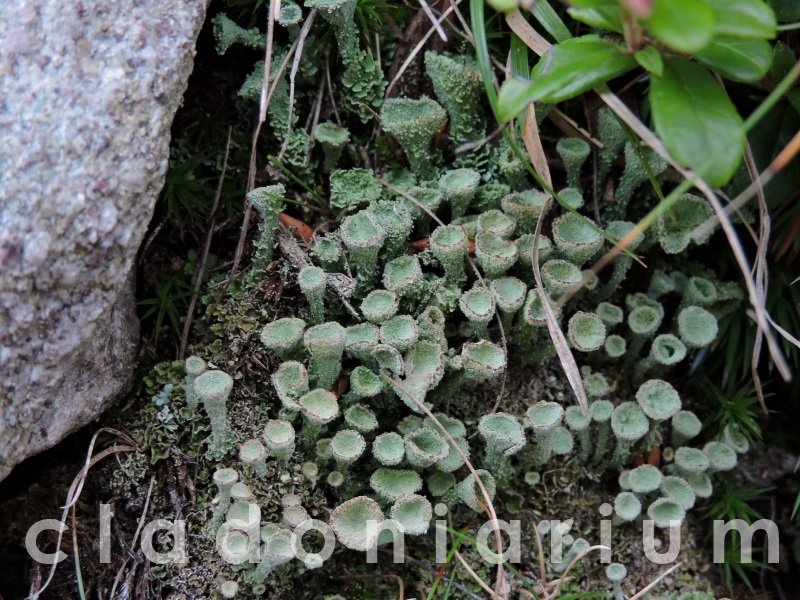

As outlined above, Cladonia peziziformis and Cladonia cariosa are very similar and easy to mistake with each other, if one has only a scarce experience about. They have both capitate podetia which bear one or more wide brown apothecia, with a range of morphological variation which is enough to create some confusion in a newcomer.

The most reliable feature to discriminate between the two species is the primary thallus: C. peziziformis has rounded or ear-shaped squamules with entire margin and procumbent posture, whereas C. cariosa has incised and generally erected squamules.

Colours are slightly different as well – since also secondary metabolites differ between the two species – since C. peziziformis is more greenish, while C. cariosa is somehow more grayish. But this feature can be misleading, so it is always better to check carefully the primary thallus.

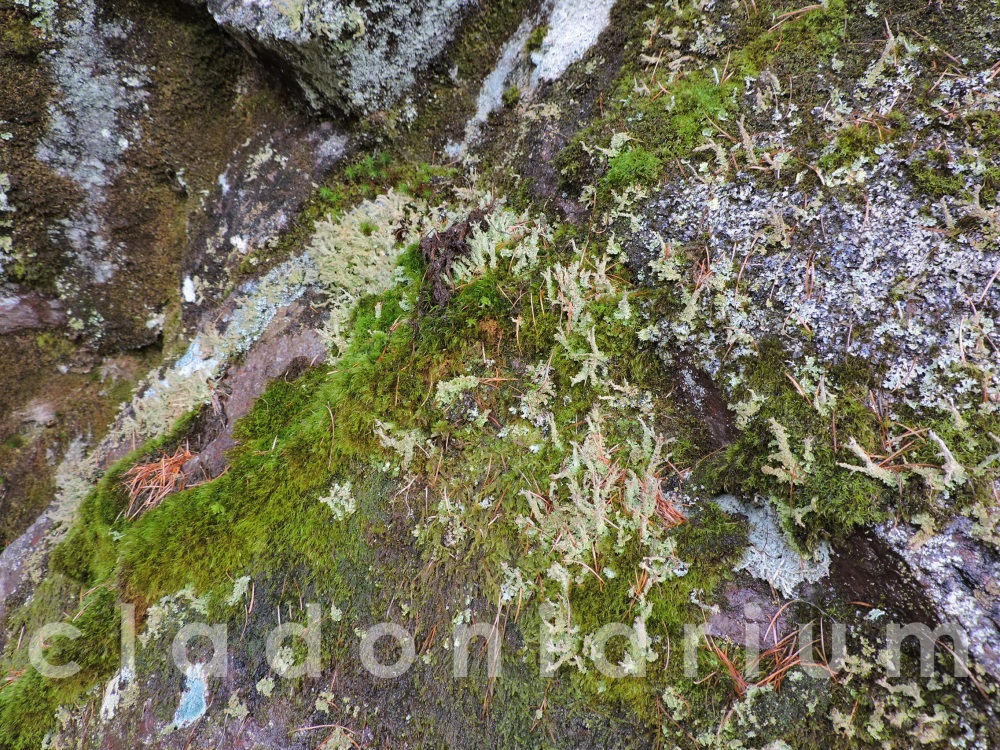

Which one is which one?!? (both the species are featured in this single shot) – In the dry grasslands on acidic sediments in the upper western Po Plain, these two species often occur together, and they characterize a particular lichen community which is typical of pioneer substrates (Gheza et al. 2019a).

A (not-so-)tiny satisfaction was also seeing that the post on the official Facebook profile of the Life Drylands project about this finding has been a great success, totalizing the highest number of ‘likes’ of all the contents ever posted on the page, and furthermore it has been shared by a considerable number of followers. I would have never expected such success for a post about tiny lichens!

I really hope that also this can contribute to increase the awareness of the general public about the urgent necessity to protect and restore natural habitats as the only efficient way to protect also many rare, sensitive and fascinating organisms like these tiny lichens.

A rich terricolous lichen community featuring C. peziziformis, C. cariosa, C. polycarpoides and C. rei scattered amongst withered tufts of Armeria arenaria.

References

Chambers S.P. 2003. Site Dossiers for the UK BAP lichens Biatoridium monasteriense, Cladonia peziziformis, Graphina pauciloculata and Schismatomma graphidioides. CCW Contract Science Report N. 586.

Gheza G. 2018. Addenda to the lichen flora of the Ticino river valley (western Po Plain). Natural History Sciences 5 (2): 33-40.

Gheza G. 2020. I licheni terricoli degli ambienti aperti aridi della pianura piemontese. Rivista Piemontese di Storia Naturale 41: 147-155.

Gheza G., Barcella M., Assini S. 2019a. Terricolous lichen communities in Thero-Airion grasslands of the Po Plain (Northern Italy): syntaxonomy, ecology and conservation value. Tuexenia 39: 377-400.

Gheza G., Nicola S., Parco V., Assini S. 2019b. La diversità lichenica nella Valle del Ticino: conoscenze in continua evoluzione. 32° Convegno della Società Lichenologica Italiana, Bologna, 18-20 September 2019, poster presentation – Notiziario della Società Lichenologica Italiana 32: 56.

Tønsberg T., Øvstedal D.O. 1995. Cladonia peziziformis new to Norway from a burnt Calluna heath. Graphis scripta 7: 11-12.

Woods R.G., Coppins B.J. 2012. A Conservation Evaluation of British Lichens and Lichenicolous Fungi. Species Status 13. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough.

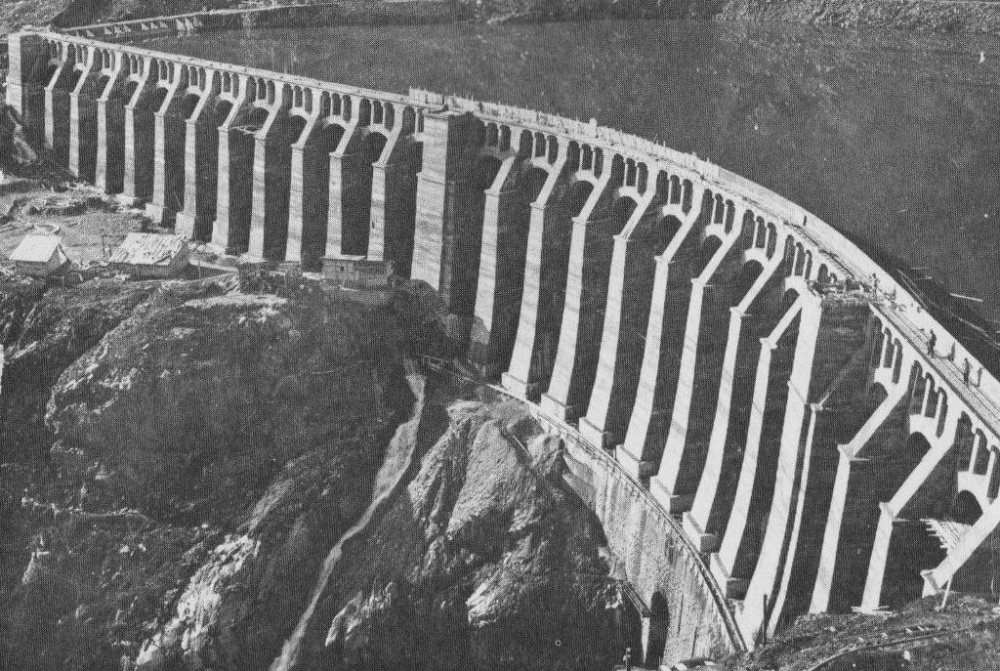

The Gleno Dam at the end of its construction, in summer 1923.

The Gleno Dam at the end of its construction, in summer 1923. A panoramic view on the easternmost Orobic Prealps from the very first part of the trail, just above Pianezza. The view ranges from the Pizzo Camino, on the far left, to the towering massif of the Mount Presolana, the “Queen of the Orobies”, on the central-right part.

A panoramic view on the easternmost Orobic Prealps from the very first part of the trail, just above Pianezza. The view ranges from the Pizzo Camino, on the far left, to the towering massif of the Mount Presolana, the “Queen of the Orobies”, on the central-right part. The Pizzo Camino Group.

The Pizzo Camino Group. The Presolana.

The Presolana.

Some Cladonias from the aforementioned heath-like vegetation.

Some Cladonias from the aforementioned heath-like vegetation. Cladonia floerkeana

Cladonia floerkeana

Lichen vegetation dominated by Cladonia pleurota and Cladonia floerkeana

Lichen vegetation dominated by Cladonia pleurota and Cladonia floerkeana Cladonia rangiferina

Cladonia rangiferina The dipping rock vault above this part of the trail. Here the view is increasingly spectacular and not recommended for those suffering from vertigo, since the trail overhangs the narrow and steep glen of the Povo stream.

The dipping rock vault above this part of the trail. Here the view is increasingly spectacular and not recommended for those suffering from vertigo, since the trail overhangs the narrow and steep glen of the Povo stream.

Cladonia cf. squamosa.

Cladonia cf. squamosa. Squamules, rachitic podetia and reddish apothecia.

Squamules, rachitic podetia and reddish apothecia. Sphaerophorus fragilis.

Sphaerophorus fragilis. The ruins of the Gleno Dam.

The ruins of the Gleno Dam.

A manual case of Cladonia pocillum, with rosulate primary thallus and schizidiate podetia.

A manual case of Cladonia pocillum, with rosulate primary thallus and schizidiate podetia. Photographing Cladonias.

Photographing Cladonias.